Why Value Public Sector Data? And How?

Detailing the need to define the value in the data we hold and the approaches we can take to measure it. Has there ever been a more pertinent time to write about valuing public sector data? With the Prime Minister declaring for the last year or more that government is “following the science” and whole […]

Detailing the need to define the value in the data we hold and the approaches we can take to measure it.

Has there ever been a more pertinent time to write about valuing public sector data? With the Prime Minister declaring for the last year or more that government is “following the science” and whole swathes of the population staring at charts and monitoring trends, the link between the data that government collects and the outcomes it drives has suddenly assumed a place at the forefront of public consciousness.

The phrase “Data Saves Lives” has long been a clarion call for those of us seeking to realise and unlock the value public sector organisations hold their data. While the concept has perhaps never felt more prescient given answers to the big pandemic questions had data at their heart, of course it’s not only in times of unprecedented uncertainty that the value in public sector data comes to the fore.

How do we deliver better care for an ageing population with changing needs? How do we predict and prevent threats to public safety? How do we move around the country more efficiently and arrest the damage we’re doing to our environment? These are questions we were grappling with before COVID-19 that will continue to challenge us as we emerge from the pandemic.

In some senses, the value in data is obvious. Unless we use it, it’s all but impossible to come up with effective and sustainable responses to complex challenges. All too often though, we struggle to prioritise the case for investment in collecting, managing and exploiting our data so that it’s ready when we need it. This is, to a large degree, due to the public sector not doing a good enough job of defining value in data and then measuring it – something the public sector needs to think creatively about articulating.

However, when one thinks of data as an organisational asset, it seems to me there are very few other assets that influence as many organisational decisions, processes and outcomes. Those that do, have entire departments looking after them and a seat at the c-suite table. HR, finance, estates and IT have been around for decades. So has data. Yet we are only just starting to see the emergence of dedicated data capabilities led by Chief Data Officers.

Why value public sector data?

Before I dive in, an important point to note – I am no economist nor asset valuation specialist. I am married to a government economist and she would delightfully declare my musings quasi economics at best – the same opinion she gave of the excellent book Infonomics by Doug Laney, from which I have taken some inspiration below. My goal then is not to help move the debate forward in a public sector context. After all, we all stand to benefit when government learns to drive greater value from its data.

Watch this video as Rich Walker explains why we should value public sector data.

Budgets aren’t limitless, so we need a way of describing what the most valuable data is and what we need to do to give us the best return on investment when improving it.”

The failure to explain, in a compelling way, where the return on data investment will be realised, is a serious issue. It’s probably the number one reason to get serious about defining and measuring the value in your data, but it’s not alone.

Other actions that drive home the point include:

1. To prioritise action

I’m a realist. Much as I see endless opportunity in data, I know there are and always will be competing priorities for investment. When it comes to choosing which bits of a data strategy to invest in, we must make choices. These should be informed by the value each initiative will individually or collectively unlock.

Do you bring in a new technology platform, begin an enterprise-wide data literacy programme or kick off the aforementioned data quality improvement project? The answer should lie in a clear understanding of the route to value. Similarly, valuing your core datasets using the approaches I’ll describe later will help you to prioritise which assets to go-after first. Not all data is equal when it comes to delivering your strategic objectives, you will need to prioritise and be able to defend those decisions to those who would have preferred you start with their area instead.

2. To measure the effectiveness of the actions you take to improve it

Just like everyone else, us data folk should be held to account for the investments we make in improving data itself (collection, curation, quality etc.) or the methods used to extract its value (analytics, digital applications etc.). Without a baseline of the value in our data, how can we persuasively present a case for the improvements we have made over time? The answer is we can’t – providing a clear need to value your data assets and revisit those valuations over time.

3. To monetise it

Not everyone will feel comfortable with the idea that public sector data assets could be commercialised in a straightforward transactional sense, but it’s unlikely to go away. The world’s wealthiest companies are data companies. Make no mistake the value in public sector data assets to those companies is monumental. It’s data they can approximate from all the other sources they mine (unless you give it to them).

Regardless of your position on this increasingly important issue (it doesn’t have to be personal data), if you were to accept a hypothetical scenario whereby a local or regional authority, for example, were to look to monetise its data, you’d want a fair price, wouldn’t you? If you were being told that part of the rationale was that this new income stream would bolster cash reserves and be ring-fenced for investment in public services, you’d want to be assured that value is fully understood – and the best deal negotiated. This won’t happen without measuring value.

How can a value be put on public sector data?

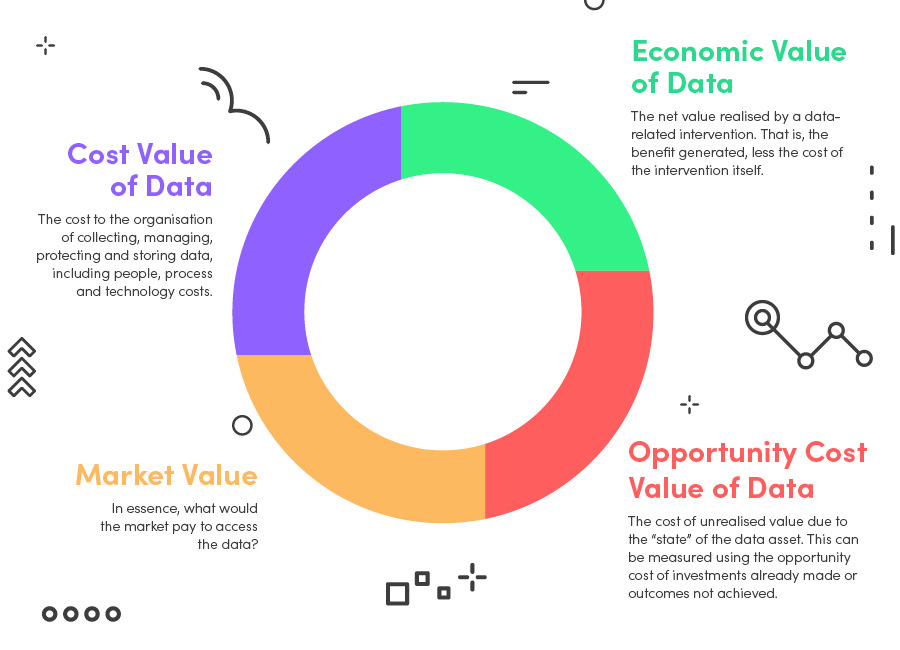

1. Cost Value of Data

The cost to the organisation of collecting, managing, protecting and storing data, including people, process and technology costs.

Speak with some sector Financial Directors and you may come across the odd one bemoaning the level of spend on what has come to be defined as DDAT expenditure. That is, spend associated with the Digital, Data and Technology capability. When you factor in the people and technology elements, it is indeed a costly endeavour.

Isn’t that a good barometer of value though? The asset that those elements fundamentally store, manage, protect, move and analyse is data. If you’re looking for a compelling statistic to use to get your investments in data as an asset taken seriously, working out how much your organisation currently spends looking after it, is a good way to get some attention. We trialled a rough and ready approach to this with a local authority recently and the results were every bit as surprising to the FD as we thought they might be.

Presenting your plan as an incremental investment (often a small percentage) to get better bang for the significant buck already committed, is a technique frequently used by those responsible for other strategic assets. I bet it wasn’t long since your last People/HR transformation as just one example. Why not sure the same approach to measure the value in your data and then argue for funds to invest in it?

The sell can take many forms, it might be that you will drive process efficiencies or performance improvements elsewhere in the organisation, or that you can identify savings and efficiencies within the current data spend portfolio but need to land an invest to save proposion.

2. Economic Value of Data

The net value realised by a data-related intervention. That is, the benefit generated, less the cost of the intervention itself.

That’s perhaps an inelegant definition, as with this approach, the value is not so much intrinsic to the data itself, but the action taken to release that value. I’ll have a bash at bringing it to life, firstly using the example I mentioned earlier of a new toll bridge and then with a data related example.

Using a logic chain to address the bridge example (keeping it deliberately simply) you would have five buckets of things to consider. The inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, impacts. Typically, the first two columns are the things that cost money and the latter three particularly the last two, are the things that either save or generate money (benefit). In the bridge example, you tot up the inputs e.g. materials and the activities e.g. construction, administration, maintenance etc. and these are your costs of the intervention. You then look at the outputs e.g. the bridge itself, regeneration of surrounding land, followed by the outcomes e.g. faster journey times, less congestion, new jobs, new business start-ups and new revenue streams and the impacts (usually directional) e.g. net additional GVA, reduced CO2 emissions, increased local employment, net additional returns to the exchequer etc.

In this context the Economic Value is the difference between those costs and benefits.

Applying this type of framework to a data related initiative is often more difficult. In commercial settings, it can be achieved through a quasi-experiment e.g. make data available to sales team ‘a’ through a new BI platform and don’t make it available to sales team ‘b’ – measure the difference in performance (e.g. monthly revenue achieved, net new clients etc) and you have a measure of value returned for your investment in the new BI stack.

When we do this with government organisations, we have tended to look at unit costs as being the most effective scaling factor for the benefits unlocked. For example, I was part of a project a few years ago where the client had an issue with delayed transfers of care from the acute hospital setting into community settings, congested wards, patients in limbo and adverse outcomes were all symptoms of what at least in part was a data problem. That is, neither party in the discharge people into, and brokerage teams had no real advance view of how many patients with which types of need they were going to need to support.

The intervention therefore was to create a live link between two systems to facilitate the exchange of data; a portal to view it through and engage the respective IG teams to ensure that relevant data protection principles were considered. The inputs (data and technology), activities (drafting and reviewing a DPIA, configuring and testing the live link, designing and building the portal) formed the costs (c€100k). The outputs, e.g. the portal itself and training for staff, the outcomes e.g. more informed decisions, better planning impacts e.g. improved patient health outcomes, reduced incidents of delays in transfer of care and improved staff morale are some of the benefits.

Now, in terms of the benefits achieved in this project, those were most strikingly captured via the concept of bed days released, to which the NHS ascribes a unit cost. In total, using the before and approach, conservative estimates suggested the trust was able to save €150,000, per month in bed days. Of course, given the challenges the NHS faces, this is not a cashable benefit, but it is a powerful example how investing in what a data and insights project was effectively could yield real tangible positive impact for an organisation facing challenges on every front.

3. Opportunity Cost Value of Data

The cost of unrealised value due to the “state” of the data asset. This can be measured using the opportunity cost of investments already or outcomes not achieved.

Let’s imagine a scenario where your organisation has made a €20m investment in a new technology platform. You were persuaded to go for the Rolls Royce version with all the bells and whistles, reassured that concerns over the data in legacy platforms were nothing the vendor hadn’t seen before and that their solution would fix all of that anyway. You’re two years into your five-year contract and to date, only 60 per cent of the functionality has been enabled. Your vendor is blaming the state of your data. In simplistic terms then the state of your data is therefore costing you €8m. Unfortunately, many will not have tp try too hard to “imagine” this scenario. This is one way in which a failure to invest in data can lead to opportunity costs, but there are others too.

A former client of mine had served 30 years in UK policing, retiring as the Chief Constable of a County Police Force. He asked me to go and talk to him about the value investing in a data strategy might unlock for his force and the wider public sector family in his patch. He dutifully gave me the floor for my finest PowerPoint, before remarking that in his 30 years as a service police Officer he had been part of many serious case reviews and that in every single one, it was possible to pinpoint instances where the better use of data, available to those organisations sat around the table, might have lessened the severity of the incident, or averted it altogether.

He pointed me to a study which suggested that each Serious Case review, over and above the deeply traumatic experiences that drove it, costs the public sector well more than €1m to undertake. That may seem an extreme example to use, but it serves as just that, an example of all the ways in which failing to invest in our data, be that collecting it, sharing it, protecting it, analysing it, quite literally costs the public sector hundreds of millions, if not billions of pounds a year.

4. Market Value

In essence, what would the market pay to access the data?

This is one of the approaches Ernst and Young took to look at the value of NHS data assets. It was more complicated than this, but effectively they looked at transactional data relating to the acquisition of data companies to approximate a benchmark for the individual health record (the cornerstone of all NHS Data). This was then scaled by the number of those records to arrive at a value. In some ways its rudimentary, but then, to say that ignores the fact that until that point, not a great deal of effort had been made to think about public sector data assets in this way and by publishing that one report, EY catalysed the debate around the value of NHS data in a way that we hadn’t seen before.

From a practical point of view, there are other means via which government can understand the market value of its data. Think about the partnerships being struck around innovative new technologies between public and private sectors. More often than not, the public sector provides the data whilst the private sector provides the means to turn it into insight and action. I believe we will see more and more of this type of “joint venture” going forwards and we’ll very quickly come to think of public sector data as a magnet to pull in private sector investment in the same way that public sector land holdings were and continue to be used as an asset in join venture property schemes.

The great thing with data though is that, in theory at least, it’s not finite (in the way for example that land is) and so the opportunity to repeatedly seat the same asset through such deals is much greater. Of course, this point ignores legitimate concerns around the ethics of using government data in this way, but my best guess tells me we’ll find a way to navigate those and end up at this reality sooner than we think.

Listen to Rich Walker as he explains how we put value on public sector data.

The most important thing to understand from my point of view is that these approaches are not designed to be mutually exclusive. To go toe-to-toe with other investment priorities, you’ll probably need as much ammunition as you can muster. If you caveat appropriately, I’m always inclined to go with the basket of indicators approach (though Economic Value and Financial Value will often be those used to carry out a formal appraisal in public sector settings).

Unique sector perspective

One final perspective pertains to the unique role of the public sector in society. For data to be taken credibly as a source of value, we must be able to talk about it in comparable terms. Leaps of faith born from wanting to do the right thing don’t cut it on their own. It’s for that reason, that I’ve deliberately focused in this article on approaches that will help you make a pounds and pence case for investment, as opposed to relying solely on the improvement in service delivery outcomes that your organisation wants to drive.

However, it is vital that in prepping yourself to cross the final hurdle and get your data programme funded, you don’t overlook the power in the human outcomes you plan to drive, be that better care, safer communities, or a cleaner environment.

Marry the two and you should have a winning formula to satisfy even the most ardent naysayer.